The glimmer of gold leaf and the hush of fervent creativity once filled the streets of Florence—a city that sparkled at the cusp of modernity yet stood firmly on the bedrock of tradition. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Florence became the cradle of a transformative cultural era known for its Renaissance art, driven in no small measure by the formidable Medici family.

The Medici Family

Their name is synonymous with artistic innovation, political acumen, and a breathtaking synergy between wealth and aesthetics. Yet as we wander through the frescoed corridors of palazzi and churches, we discover that the Medici influence on art transcended the mere commissioning of beautiful objects. It touched upon the very soul of creativity, fuelling a dynamic interplay of patronage, power, and philosophical depth that still captivates our collective imagination.

In this exploration, we shall delve into how the Medici family legacy was woven into the fabric of Florentine life, transforming the city into a masterpiece of human ingenuity. We will also consider the perspectives of modern thinkers such as Leon Trotsky, Vladimir Lenin, and Walter Benjamin, whose writings on art and culture prompt us to re-evaluate the commercial and ideological layers behind grand patrons and grander artworks. In this manner, we take a journey through the gilded halls of Florence to understand what happens when art becomes not only a testament to devotion and beauty but also a mirror reflecting broader social and economic forces.

Florence at the Dawn of a New Age

When we speak of art and power in the Renaissance, Florence often emerges as the quintessential stage—its narrow, winding streets and lively piazzas alive with merchants, scholars, artists, and political operatives. It was a city of burgeoning trade, famed for its wool and silk industries, and a rich mercantile spirit that shaped its rising middle class. Yet the spiritual and aesthetic transformation of Florence would not have occurred without the robust network of financial patronage that sustained the city’s artistic fervour.

At the heart of this network lay the Medici family. Originally prominent bankers, they amassed wealth and influence on a scale seldom seen. The Casa Medici rose to become one of the most prosperous banking institutions in Europe, with branches stretching from London to Rome. As the family’s coffers grew, so did their political ambitions. By forging alliances within the Florentine Signoria and maintaining cordial relationships with the papal court, the Medici effectively steered the course of Florentine governance. Their ascendancy, however, was not solely political; it was imbued with a vision of using wealth to foster a flourishing culture of Renaissance art.

Cosimo de’ Medici: The Visionary Patron

The story of Medici patronage begins in earnest with Cosimo de’ Medici (1389–1464), often called “Cosimo the Elder.” Known for his affable personality and shrewd political mind, Cosimo recognised that controlling Florence went beyond mere financial manoeuvring. He understood that true power lay in shaping the intellectual and cultural climate of the city.

Cosimo financed architectural endeavours that remain icons of Medici family legacy. For instance, he commissioned Filippo Brunelleschi to work on the San Lorenzo Church, supporting a style that embraced classical harmony and proportion. To the Florentines of the time, this new architectural language evoked a rediscovery of ancient Roman ideals, aligning with the nascent concept of humanism. Through patronage, Cosimo sought to elevate the city’s collective identity, turning Florence into an emblem of refinement, intellect, and creative prowess.

Yet patronage was not merely a philanthropic pursuit; it also served as a strategy for securing political goodwill. Florentine artists, architects, and intellectuals were beholden to the Medici purse. In reflecting on such relationships, thinkers like Leon Trotsky (1879–1940) have argued that art often reflects the socio-economic structures in which it is created. While Trotsky’s analyses primarily addressed the era of revolutionary Russia, his insight resonates across centuries: artistic output can be swayed by those controlling the means of production—in this case, wealthy patrons like the Medici.

Lorenzo de’ Medici: The Magnificent Legacy

If Cosimo laid the foundation of Medici influence on art, Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449–1492), often known as “Lorenzo the Magnificent,” transformed that foundation into a resplendent edifice. Lorenzo was a celebrated patron of artists such as Sandro Botticelli, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and Leonardo da Vinci. His court at the Medici Palace sparkled with poetry, music, and philosophical debates—a true microcosm of art and power in the Renaissance, where luminaries mingled with political figures and theologians alike.

A Circle of Genius

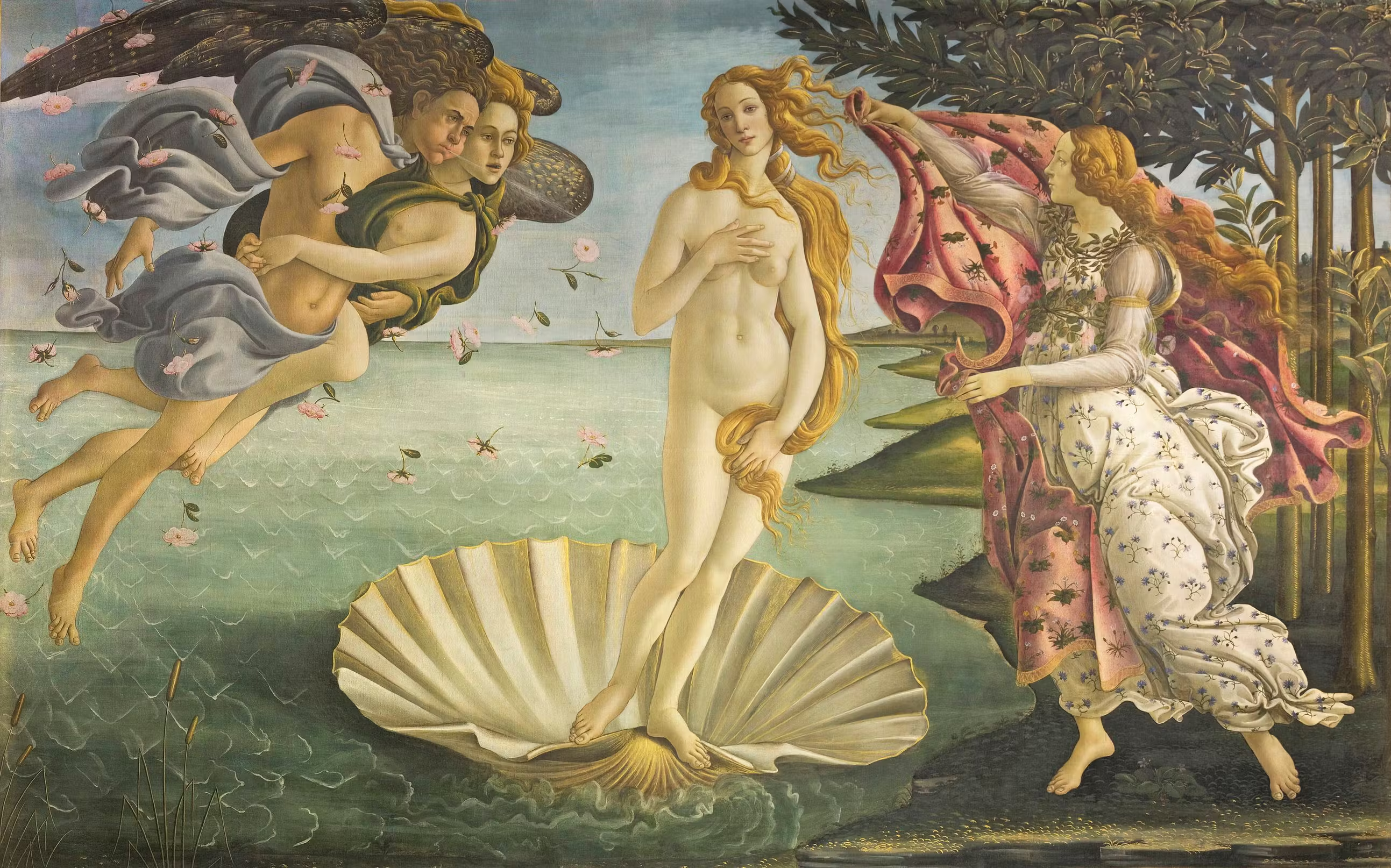

Under Lorenzo’s stewardship, Botticelli’s ethereal lines and Michelangelo’s chiselled genius came into full bloom. Botticelli’s “Primavera” and “The Birth of Venus” exemplified the renewed passion for mythological themes, replete with classical references yet suffused with a grace that felt quintessentially Florentine. Lorenzo’s love for Platonic philosophy also influenced the intellectual climate, leading scholars like Marsilio Ficino to translate and comment upon Plato’s works, thereby blending the pagan wisdom of the ancients with Christian theology.

Michelangelo’s Formation

Perhaps the most poignant example of Medici influence on art emerges in the life of Michelangelo Buonarroti. Taken under Lorenzo’s patronage at a young age, Michelangelo studied the Medici art collection and honed his craft in the sculpture garden directed by Bertoldo di Giovanni, a disciple of Donatello. This direct exposure to classical statues and Medici patronage shaped Michelangelo’s distinctive style, characterised by its muscular forms and an almost divine grandeur. Indeed, had it not been for Lorenzo’s unwavering support, the Renaissance might have been deprived of the sublime force of Michelangelo’s David or the majestic ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Patronage as Soft Power

Lorenzo’s court exemplified how patronage could function as soft power. Hosting philosophers, poets, and artists bolstered the Medici’s prestige and embedded them in a cultural network far more enduring than ephemeral political alliances. This interweaving of patronage and political strategy resonates with the reflections of Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), who, though primarily engrossed in the revolutionary ideas of the early twentieth century, understood the potency of cultural symbols in shaping ideology. From Lenin’s vantage, art patronage could be appropriated by the ruling classes to reinforce their dominance. The Medici’s display of magnanimous support for the arts thus served to legitimise their authority, presenting them not as ruthless oligarchs but as benevolent custodians of beauty and knowledge.

Art as Commodity and Ideology

While the Medici exemplify a triumphant patronage model, their story also raises deeper questions about how wealth shapes artistic production. Walter Benjamin (1892–1940), the German literary critic and philosopher, wrote extensively on art’s transformation in the age of mechanical reproduction, focusing on its loss of “aura” as it became more widely disseminated. Although Benjamin’s analysis concerned industrialised societies, one can perceive early stirrings of art’s commodification in the Renaissance.

Banking, Bargaining, and the Arts

The Medici family built their fortune primarily through banking. The financial system of letters of credit, currency exchange, and interest was expanding across Europe, and the Medici were at its forefront. Artworks could thus be seen not just as expressions of individual genius but also as assets, consolidating family status and forging beneficial alliances. A bishop or nobleman impressed by a commissioned altarpiece might become a more favourable business partner or political ally in the future. In this context, an artwork had dual values: aesthetic and transactional.

The Role of Reputation

Reputation mattered greatly to Renaissance patrons. A painting by Botticelli or a sculpture by Donatello served as a kind of advertisement for the commissioner’s taste, refinement, and power. This synergy between commercial exchange and aesthetic accomplishment resonates with Trotsky’s view that art while possessing the capacity to inspire and transform, is also shaped by the “infrastructure” of its time.

Put plainly, the very possibility for Botticelli to create his dreamlike canvases was contingent on a system of wealth and patronage that made such endeavours economically viable. In Lenin’s framework, one might go further to argue that the patronage system subtly propagates a worldview that sustains the patrons’ social hegemony, presenting their reign as the natural wellspring of beauty and culture.

Florence as a Cultural Epicentre

For the people of Florence, these commissions redefined the look and feel of the city. It was not unusual for crowds to gather around a new fresco or altarpiece, marvelling at the lifelike figures that seemed to gaze back from the walls. Churches like Santa Maria del Fiore and Santa Maria Novella became living galleries, showcasing the prowess of Florentine masters.

Civic buildings, private chapels, and public squares were likewise illuminated by fresh artistic visions, each financed in part by the Medici or other wealthy families hoping to rival or curry favour with them. Thus, the ephemeral lines between private patronage and collective cultural heritage blurred, as the city’s aesthetic blossoming was both a public spectacle and a testament to private ambition.

Shifts in Medici Fortunes and Lasting Impact

Exile and Return

Despite their cultural stature, the Medici were not immune to political upheaval. In 1494, shortly after Lorenzo’s death, the family was exiled from Florence under the wave of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola’s puritanical regime. The city underwent a brief period of fervent religious reform, wherein secular art and worldly luxuries were denounced. Yet, in an extraordinary twist, the Medici would eventually return to power through various machinations, including alliances with powerful European dynasties and the papacy. Their exile and subsequent restoration underscored the precarious balance between the populace’s admiration for Renaissance art and the discontent that wealth-based power could ignite.

Becoming Dukes of Florence

Over time, the Medici transformed from merchant bankers into hereditary rulers. In 1537, Cosimo I de’ Medici established the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, marking a shift from the veneer of republican governance to outright dynastic rule. This shift also corresponded with the later stages of the Renaissance when Mannerism began to supplant the classical harmonies championed by earlier masters. Yet, even as art evolved, Medici’s influence on art persisted. The Medici funded sprawling architectural projects such as the Uffizi, which would become one of the world’s first modern museums. Thus, while the political structure changed, the family’s commitment to shaping Florence’s cultural life remained steadfast.

The Medici Family Legacy in Europe

The Medici’s impact rippled across Europe. Their daughters married into royal families in France and beyond, carrying with them an air of Florentine sophistication. One notable figure was Catherine de’ Medici, who, as Queen of France, patronised the arts and even influenced culinary traditions (introducing certain Italian dishes and table manners to the French court). Through these royal marriages, the Medici helped disseminate the ideals of the Renaissance far beyond the banks of the Arno. Palaces were built in the Florentine style, painters travelled to other courts, and the humanist philosophies championed by Ficino and others found fertile ground on the continent.

Art and Philosophy: A Dialogue Across Centuries

Patronage and the Shaping of Ideology

To revisit the theoretical triad of Trotsky, Lenin, and Benjamin, one sees in the Medici era a vivid illustration of how art patronage can indeed serve as a vehicle for cultural hegemony. Yet it would be an oversimplification to suggest that artists merely reproduced the will of their patrons. As we see in Botticelli’s mythological reveries or Michelangelo’s singular style, the spirit of creative genius and humanist thinking cannot be fully contained by wealth or politics.

Lenin’s cautionary stance on art as a tool of the ruling classes and Trotsky’s analysis of art’s dependence on economic structures remind us that creative expressions are often tethered to broader socio-political realities. Walter Benjamin’s reflections on the commodification of art prompt us to see how even in the Renaissance—a time far removed from mass production—artworks were part of a system of exchange and display. Although Renaissance artists did not labour under industrial conditions, they still participated in a form of cultural production shaped by patron demands and market forces.

The Sublime and the Political

Nevertheless, Renaissance artworks also carry a timeless sublimity. Standing before Michelangelo’s David or gazing upon the luminosity of Botticelli’s Venus, one experiences a moment of transcendence that seems to outstrip any narrow economic or political framework. In truth, these layers of meaning—spiritual, philosophical, political, and aesthetic—coexist within Renaissance masterpieces, creating a tapestry that beckons us to consider art in all its complexity. Here lies the enduring power of the Medici family legacy: the synergy between creative liberty and patronage, between the fullness of human expression and the constraints of realpolitik.

Florence as a Cultural Palimpsest

Even centuries after the last Medici ruler, Florence remains a living gallery of Renaissance art. Tourists from around the globe wander through the Uffizi Gallery to behold Botticelli’s paintings, each brushstroke evoking an age when the interplay of mythology, religion, and civic pride sparked a visual revolution. A short stroll away, the Medici Chapels in the Basilica of San Lorenzo showcase Michelangelo’s sculptural prowess, their marble figures imbued with an almost ethereal grace. Every brick and fresco in the city bears the imprint of the Medici influence on art, attesting to how profoundly patronage can mould a culture’s legacy.

Yet this legacy is not confined to the city’s boundaries. The intellectual currents that were nurtured in Florence fanned out across Europe, fertilising the seedbed of modern Western civilisation. The Medici, with their vaults of gold and nuanced understanding of power, ignited an artistic flame that illuminated cathedrals, palaces, and civic spaces far beyond Tuscany. An argument can be made that, without the Medici’s strategic fostering of humanist ideals, the course of European art and thought might have followed a markedly different trajectory.

Reflecting on Art and Power in the Renaissance

To ponder the Medici story is to wrestle with the complex dance between creation and commerce, between boundless inspiration and calculated strategy. The Medici family harnessed wealth and political clout to elevate Florence’s artistic life, proving that the scaffolding of commerce can support breathtaking achievements in culture. Yet their story also invites us to question who controls the narrative of art. Do those who finance culture also dictate its philosophical underpinnings, or can the artistic spirit break free from the confines of patronage?

From a Marxist perspective, Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin might argue that art remains bound to material realities, shaped by the hands that feed it. Walter Benjamin’s cautionary reflections remind us that when art is circulated as a commodity—whether in the fifteenth century or the era of digital reproductions—something of its ephemeral aura risks being lost or transformed. And yet, standing in the hushed interior of the Basilica di Santa Croce or marvelling at the Duomo’s soaring dome, one senses a timeless beauty that transcends ideological frames. These dualities—to be both commodity and transcendent force—illustrate the enduring enigma of Renaissance art.

Ultimately, the Medici’s feats underscore how an affluent and politically astute family can leave an indelible mark on civilisation. The Medici family legacy is neither wholly celebratory nor purely cautionary; it is, rather, a testament to the power of patronage in shaping the physical, intellectual, and spiritual landscape of an era. Through their lavish commissions, the Medici reaffirmed Florence’s status as the epicentre of art and power in the Renaissance—a place where philosophical questions about beauty, faith, and governance continue to find expression in every fresco, sculpture, and façade.

Indeed, art and power have danced together throughout history, their steps sometimes measured, sometimes tumultuous. In Renaissance Florence, this dance reached a crescendo, as the Medici orchestrated a symphony of painterly visions and architectural marvels that still resonate with us today.

Their story invites us to reflect on the unbreakable bond between vision and patronage, creativity and commerce—a bond that, for better or worse, underscores how our greatest cultural triumphs often emerge from the interplay of lofty ideals and earthly resources. And so, centuries on, the Medici stand as living reminders that beauty, once brought into the world, transcends its origins, glimmering through time as a beacon of both humanity’s highest aspirations and the power structures that shaped them.

Keep Independent Voices Alive!

Rock & Art – Cultural Outreach is more than a magazine; it’s a movement—a platform for intersectional culture and slow journalism, created by volunteers with passion and purpose.

But we need your help to continue sharing these untold stories. Your support keeps our indie media outlet alive and thriving.

Donate today and join us in shaping a more inclusive, thoughtful world of storytelling. Every contribution matters.”